For thousands of years, cow’s milk contained just one type of protein – until a genetic shift changed dairy history. Today, a growing number of producers are returning to cattle genetics that yield what many consider milk’s original form. This specialty dairy product skips a specific protein linked to digestive discomfort, offering an alternative for those sensitive to conventional varieties.

Australian and New Zealand farmers pioneered commercial production of this variety in the early 2000s. Their work created a premium market segment that’s now expanding globally, particularly across Asia. Recent projections show North American sales could surge by nearly 19% before 2027.

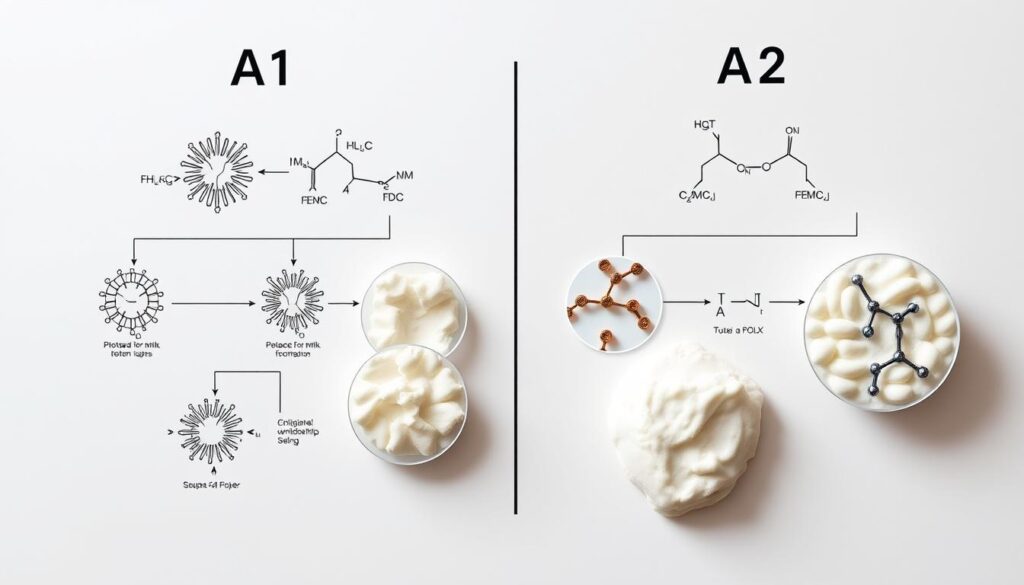

The key difference lies in beta-casein proteins. While standard milk contains both A1 and A2 types, this version retains only the latter. Some nutrition experts suggest this simpler protein structure may support easier digestion without eliminating dairy from diets entirely.

For rural producers, the appeal is clear. Transitioning herds to A2 genetics can create value-added products that attract higher prices. As one Queensland dairy farmer notes: “It’s about meeting consumer demand while maintaining our operations’ viability.”

Key Takeaways

- Originates from cattle genetics unchanged by historical protein mutations

- Asia Pacific markets drive global demand growth

- Australian innovators lead commercial development

- Contains only A2 beta-casein protein

- Offers premium pricing opportunities for producers

- Appeals to consumers seeking digestive comfort

Understanding A2 milk and Its History

The journey of milk proteins began with a single type, until evolution introduced a new variant. All dairy once contained only the original beta-casein structure, but a genetic mutation thousands of years ago created a distinct protein found in many herds today.

Origins and Evolution of Beta-Casein

Beta-casein accounts for nearly one-third of cow’s milk proteins. Jersey and Guernsey breeds naturally retain higher levels of the original protein type, while Holstein-Friesian cattle – the backbone of commercial dairying – predominantly carry the newer variant. “Our work revealed that not all milk proteins behave the same in the human digestive system,” explains Dr. Corran McLachlan, part of the New Zealand research team behind the 1993 discovery.

From Traditional to Modern Milk Production

Before industrial farming, traditional breeds dominated milk production. Today’s operations favour high-yield Holsteins, leading most supermarket varieties to contain mixed proteins. Selective breeding programs now help farmers identify cattle that produce milk with only the original protein structure. DNA testing of hair samples ensures herds meet strict genetic standards, maintaining dedicated supply chains for this specialised dairy product.

New Zealand researchers pioneered methods to verify protein types, giving producers tools to adapt their herds. As one Victorian dairy manager notes: “Testing lets us breed smarter, not harder – that’s progress that respects both science and tradition.”

The Science and Research Behind A2 milk

Groundbreaking discoveries are reshaping how we understand milk’s biological effects. Over 25 peer-reviewed studies now examine how different protein types interact with human digestion – findings that matter for both consumers and producers.

Breaking Down Beta-Casein Behaviour

When A1 proteins break down during digestion, they release BCM-7 – a compound linked to stomach inflammation in sensitive individuals. A 2016 Australian study found this peptide appears in blood samples 40% faster after consuming conventional dairy versus A2-only products.

Indian researchers made critical discoveries using lab mice. Subjects fed A1 proteins produced three times more inflammatory markers than those on A2 diets. “The difference in gut responses was undeniable,” notes Dr. Ramesh Kumar from the National Dairy Research Institute.

Protein Structures Under the Microscope

Though A1 and A2 proteins differ by just one amino acid, this variation changes how they behave:

- A2 breaks down smoothly during digestion

- A1 forms BCM-7 fragments that may enter the bloodstream

- Human trials show reduced bloating with A2 consumption

A 2019 analysis of 20+ studies concluded there’s moderate evidence linking A1 proteins to digestive discomfort. However, experts caution more independent research is needed, particularly regarding long-term effects.

“We’ve observed clear patterns in lactose intolerance symptoms improving with A2 dairy. But farmers should consult multiple sources before altering herd genetics.”

A2 milk: Health Benefits for the Family

Emerging research highlights how specific milk proteins impact both gut health and cognitive function. A 2021 clinical trial involving 120 Chinese adults with dairy sensitivity revealed striking differences between conventional and alternative dairy consumption.

Gut Comfort and Cognitive Performance

Participants consuming standard dairy reported 68% more abdominal pain compared to those using the specialised product. Stool consistency improved significantly in 83% of trial subjects switching protein types. Blood tests showed 40% lower inflammation markers in those avoiding mixed proteins.

The study’s cognitive assessments proved equally revealing. Reaction times slowed by 15% after conventional dairy intake, with error rates doubling during problem-solving tasks. “These findings suggest protein choice affects more than digestion,” notes lead researcher Dr. Wei Zhang.

Complete Nutrition Without Compromise

This dairy alternative matches conventional options in essential nutrients:

- Equivalent calcium levels for bone health

- Identical vitamin B12 content

- Comparable protein quantities per serve

Families with sensitive children report fewer complaints about stomach aches during school days. However, producers caution it’s not suitable for those with diagnosed lactose intolerance. As one NSW nutritionist advises: “Consider protein sensitivity before eliminating dairy entirely.”

Practical Tips for Integrating A2 milk into Your Diet

Managing digestive sensitivities requires careful planning. Australian nutrition guidelines reveal most individuals can handle 250ml of lactose daily when spread across meals. This creates opportunities for gradual reintroduction of dairy-based foods.

Balancing Tolerance Levels

Start with 50ml servings of specialised dairy alongside meals. Combine it with oats or eggs to slow digestion. Track reactions over 72 hours before increasing quantities. “The key is patience,” advises rural dietitian Tanya Wilkins. “Gut adaptation takes time, but many find they can enjoy dairy again.”

Everyday Meal Solutions

Replace regular milk in morning coffees first – the smaller volume helps test tolerance. For baking, use equal measures in scones or pancakes. Consider these practical swaps:

- Blend into smoothies with banana and peanut butter

- Mix with rolled oats overnight for breakfast

- Create creamy sauces using cornflour as thickener

Families report success by introducing one dairy meal daily, like cheesy vegetable bakes. Remember: severe lactose intolerance requires medical guidance. Always consult health professionals before making dietary changes.

Conclusion

Innovations in dairy genetics have reshaped how producers meet modern consumer needs. The milk company that pioneered this movement, originating in New Zealand over twenty years ago, now sees North American revenues doubling within single financial years. Rigorous DNA verification of cattle herds ensures products meet strict protein standards, creating trusted dairy alternatives for sensitive consumers.

Market projections suggest sustained 18% growth as awareness spreads. While studies highlight reduced digestive discomfort for many people, producers should note most research comes from industry-funded sources. Independent analysis remains crucial for understanding long-term effects and potential risks.

For Australian cattle operations, transitioning herds requires strategic planning. Genetic testing costs and breed selection impact profitability, but premium pricing offsets initial investments. As one Queensland producer observes: “Specialised dairy isn’t a trend – it’s answering real consumer needs with science-backed solutions.”

The success of this company limited model demonstrates agriculture’s capacity to evolve through targeted innovation. Rural families gain nutritional options, while producers access growing markets – a practical balance of tradition and progress.